We are finally able to share the first of (hopefully!) two articles we have been preparing this summer on the topic of cooling hot dogs. This summer has seen the usual barrage of social media posts promoting canine cooling myths, with some big names in the UK veterinary world doing their best to dispel the ongoing myth that cold water cooling is dangerous for dogs. We were also approached by a “fact checking” organisation to comment on the “did you know” post that advocated for cooling using only damp towels, so here is our take on cooling hot dogs using the best available evidence from the scientific literature.

Veterinary Guidelines:

In 2016, the The American College of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care’s Veterinary Committee on Trauma (Vet-COT) published “prehospital” care guidelines for managing dogs and cats. In other words, a group of veterinary critical care specialists came together to scour the best available scientific evidence to develop guidelines for providing emergency care to pets before they could be transported to a veterinary practice. These guidelines made two key recommendations:

1 – Cool first, transport second.

2 – Cool using water, either cold-water immersion for young/healthy dogs, or evaporative cooling (application of water alongside air movement from a fan/air conditioning/breeze) for older/unwell animals.

For clarity, this is cold-water immersion:

Ronin here (in the image) is post canicross race, and has elected to immerse himself in the available water bath, lying down and staying here until he felt ready (cool enough) to get out! Anne and Emily have observed years of canicross races, and dogs will literally drag their humans towards lakes, streams, ponds, paddling pools, whatever cold-water is available for cooling. And that water is COOL, we measured a lake with water at 0.5˚C, and the dogs ran straight in and stayed there until they were ready to get out, in December.

Cold-water immersion is the recommended treatment for exertional HRI (heatstroke) in human athletes too.

Evaporative cooling looks different depending on the resources available, but here Ares the Malamute is demonstrating evaporative cooling using a hose pipe and electric fan:

In a true emergency situation if you don’t have a means of immersing the dog in cold-water, or if the dog is unwell/unconscious (drowning is a very real risk for unconscious dogs in water), then evaporative cooling is the next best option. Apply whatever water you have (provided the water is cooler than the dog), and ensure the dog is out of the sun, but has air movement from either a fan, the breeze or air conditioning.

Myth busting – is cold water cooling really dangerous?

No.

Cold-water immersion is the recommended cooling method for young, healthy individuals with HRI (heatstroke). There is a wealth of evidence from equine and human medicine to support cold-water cooling as the most effective treatment for profound hyperthermia.

In dogs, there may be less evidence, but the research available supports cold-water cooling. We’ve talked about a study published in 1980 before, and whilst this study would not receive ethical approval by today’s standards, the results need to be remembered. Conscious dogs with HRI cooled faster in 1-16˚C water, than they did in 18-25˚C water. Comatose dogs with HRI had the highest rate of cooling in 1-3˚C water, but it should be noted that comatose dogs cooled slower than conscious dogs. This is because comatose dogs stop panting, and panting is a vital method of thermoregulation for hot dogs.

That being said, any water (cooler than the dog) is better than no water.

A study of military working dogs compared cooling dogs by immersion in 30˚C water (what would be room temperature water in hot environments), with letting the dogs rest in front of a fan, or rest on a cooling mat in front of a fan. Immersion in 30˚C water resulted in significantly faster cooling post exercise. So the message is clear, use whatever water you have available, provided it is cooler than the dog.

Myth busting – are water-soaked towels the best option?

No.

That being said, we don’t actually have any strong evidence evaluating the effectiveness of water-soaked towels as a cooling method in dogs, we’re extrapolating research from other species. In horses, water-soaked fabric sheets were compared against evaporative cooling, and simply standing the horse to rest. There was no difference in cooling rate between the horses “cooled” using water-soaked sheets, and those simply standing to rest. In humans, iced wet towels are recommend to facilitate athlete cooling in rest breaks during exercise (for example football players between time on pitch), but this was for prevention of HRI, not treatment should HRI develop.

In short, applying a water-soaked towel is better than doing nothing, but cold-water immersion or evaporative cooling are the preferred method for cooling dogs with HRI in an emergency.

In dogs, water-soaked towels can also be used to facilitate keeping dogs cool to prevent HRI. Here Quinn the Cav is keeping cool in 35˚C heat in the UK, by staying in the shade, drinking plenty of water, making the most of the breeze, and wearing a continually soaked evaporative cooling vest. Crucially, the cooling vest was used to PREVENT heating at rest, not as a treatment for HRI.

The problem with cooling vests, and placing water-soaked towels over hot dogs, is that the dog can’t remove the vest/towel. So once the vest/towel dries out, it is no longer providing any cooling action, they require constant wetting to be effective. A towel placed over a dog will prevent air circulation to the skin, so once the towel is dry it will limit further convective cooling.

For thick coated dogs, the hair will limit the towel’s contact with the skin, so will limit cooling. Below, Ares is demonstrating an alternative, placing the water-soaked towel UNDER the dog. The towel is in better contact with the thinly haired regions on the abdomen and legs, and Ares can get up and walk away when he wants to. Again, this water-soaked towel is being used to keep Ares cool to prevent him overheating, not to treat HRI.

Myth busting – should you immediately transport a hot dog for treatment?

In an emergency, the advice is usually to seek veterinary treatment ASAP. On the whole this is excellent advice. However, for both humans and dogs with HRI, the recommended action is “Cool first, transport second”.

In human medicine, a recent study in the US found a mis-match between the sports medicine recommendation to “cool first, transport second”, and the emergency medicine first responder guidelines for managing patients with HRI which prioritised transporting patients to hospital for cooling. So who is right?

Two large human hospital studies from Japan and China have demonstrated that active cooling reduces mortality in patients with HRI, and rapid cooling in the first 2 hours of HRI treatment improves survival. In dogs, we know that both the degree of body temperature elevation above 43˚C, and the duration of temperature elevation above that critical threshold predicts HRI severity. In other words, the longer the dog’s temperature remains critically elevated, the more severe the damage. Therefore, rapid cooling should be a priority to limit the potential for thermal damage, and limit the severity of HRI.

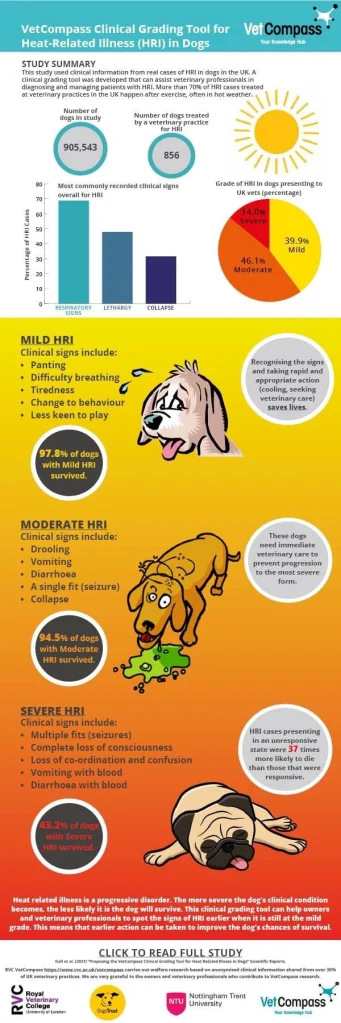

From our previous work we know that dogs presenting to vets with severe HRI had 65 times the odds for death compared to dogs presenting with mild HRI. Less than half of the dogs presented to vets with severe HRI survived.

Cooling myths are harming dogs.

Our latest study reviewed the clinical records of dogs presented to primary care (GP) vets in the UK during 2016-2018, to explore the cooling methods being used to manage dogs with HRI. First things first, we should note that those US Vet-COT guidelines from the start of this post were only published in 2016, so it should come as little surprise to anyone that they hadn’t fully disseminated into UK vet practice.

What did we find? Firstly, just 21.7% of dogs presented for veterinary treatment of HRI had been cooled prior to transport. So the rest of those dogs experienced a delay before being actively cooled, meaning they stayed hotter for longer. The message to “cool first, transport second” needs to be prioritised in first aid advice for managing dogs with HRI. On a more positive note, of those dogs cooled prior to transport, only 10.8% required further cooling by the veterinary practice on arrival. Over 50% of dogs cooled by their owner received active cooling used water (cold-water immersion, water spray, or evaporative cooling).

Overall, just 24.0% of dogs were cooled using the Vet-COT recommended methods – cold-water immersion or evaporative cooling. In contrast, 51.3% of dogs were cooled using water-soaked towels. Now, we didn’t attempt to analyse the effectiveness of those cooling methods, as this was a retrospective study and there are too many factors to consider in that analysis. But we can say with certainty that the myth that water-soaked towels are the best option for cooling hot dogs has influenced how people manage dogs with HRI, despite there being NO SOLID EVIDENCE to support this myth.

What next?

Whilst we’re busy analysing our other cooling study, we have two clear messages for anyone living or working with dogs. If you are faced with a dog that develops HRI:

- Cool first, transport second. By all means phone the vets immediately, but don’t leave the dog hot whilst they travel.

- Use water to cool the dogs:

- Cold-water immersion for young/healthy dogs.

- Evaporative cooling (water application plus air movement) for any dog.

We end with an image from Chiara Di Giorgi, which illustrates evaporative cooling for a cat 🙂 This elderly cat has a nasty habit of falling asleep in a very hot conservatory (remember older animals are at increased risk of HRI, cats over 15 years of age especially), and has been treated for HRI previously… thankfully on this occasion rapid, active cooling using evaporative cooling (water application and air movement) saved the day.