Our second article on cooling hot dogs has been published, so as the UK weather turns warmer, now is the time to re-fresh your knowledge on the latest evidence on cooling hot dogs:

Post-exercise management of exertional hyperthermia in dogs participating in dog sport (canicross) events in the UK

We’ll start by thanking all of the dogs (and their owners) who participated in this study, as we couldn’t have done it without them! The study involved measuring ear temperature (more on this in our previous post) at three time points – 0-minutes (immediately after the dogs crossed the finish line), 5-minutes (after any initial post-exercise cooling) and 15-minutes after exercise – the dogs completed canicross races or training events in the UK. We asked owners to tell us how they managed their dogs in the period immediately after exercise, including any cooling actions and if the dog was housed in a vehicle, whilst we measured both the dogs’ temperatures and the ambient weather conditions. Just to be clear, when we say dogs were housed in vehicles, they were under direct supervision at all times and most of the events took place in the winter, in the early morning before ambient temperatures had started to rise. At some events, dogs were housed in vehicles to stop them getting too cold – especially the thin coated Lurcher types!

We observed five main approaches to post-exercise management of canicross dogs: water immersion, walking the dog outside, standing the dog outside, applying a cooling jacket, and no cooling (dog housed immediately in a vehicle).

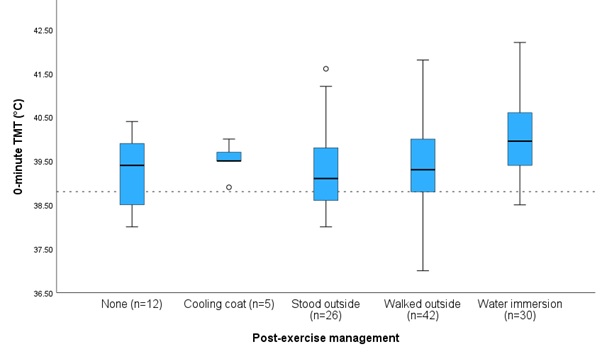

As you can see, there was a lot of variation in post-exercise body temperature, with dogs finishing the events with ear temperatures measuring anywhere from 37.0 to 42.2°C. It is also worth noting that most of the events took place during the autumn-winter racing season in the UK, the ambient weather conditions (measured using wet bulb globe temperature) ranged from 0.4 to 24.6°C with a median temperature of 8.5°C. Before you consider judging the owners who took no cooling action, remember there was snow on the ground for some of these events, and no dogs suffered any adverse effects from either the exercise, or post-exercise management during the course of the two-year study.

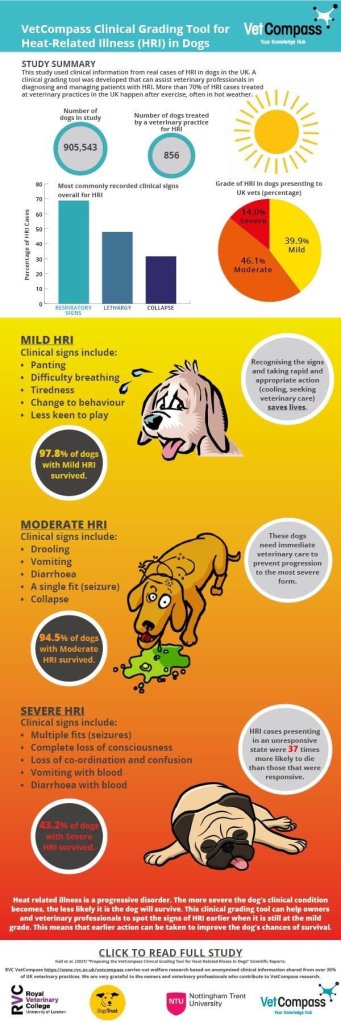

A key finding we would like to highlight to all dog owners, is that around a quarter of the dogs had peak temperatures measured AFTER the exercise had finished, despite being cooled. Why is that important? The reason our core body temperature continues to rise after exercise is due to heat from the muscles being gradually re-distributed around the rest of the body by the blood circulation. Had we measured the dog’s muscle temperature immediately post-exercise, there would have been a difference between muscle and ear temperature, and that difference would have reduced as time progressed. Back to why that is important! We know both the degree of core body temperature elevation above 43°C (just how high the dogs temperature reaches), and the duration of elevation (how long the dog’s temperature remains critically high) contribute to disease severity and fatality from heat-related illness. One of the most heat-sensitive tissues is the brain, and brain damage can prove fatal to dogs with heatstroke. So the longer we allow the dog to remain hot, the more muscle heat can redistribute raising the dog’s core temperature, increasing the risk of severe heat-related illness. If you observe early signs your dog may be developing heat-related illness, simply stopping exercise may not be enough as their core temperature could continue to rise as the heat from their muscles redistributes to the rest of the body.

So which cooling method is best?

Unfortunately, we can’t answer that question from the results of this study; because this was an observational, field based study, the ambient weather conditions varied, the dogs themselves took part in different length races, the water for cooling varied by temperature at each event, and the cooling methods used by their owners were not standardised. In addition, if you look at the box-plot above, its probable the dog’s post-exercise temperature influenced their owner’s decisions about which cooling method to use. In addition, some dogs self-selected water immersion as the cooling method which, again, may have been influenced by their body temperature.

Whilst we can’t definitively say cold-water immersion is the most effective cooling method based on our study, there is a wealth of literature from humans, horses and dogs (see our previous post) to support cold-water immersion as the most rapid way to reduce body temperature.

We can, however, report we observed no adverse effects in any of the dogs cooled using cold-water immersion in our study, and can confidently report cold-water immersion is an effective cooling method for hot dogs. The water available for cooling ranged from 0.1 to 15°C, so would be defined as “cold” as opposed to “tepid”. Many dogs entered this water voluntarily (or should we say enthusiastically!) and remained in the water throughout the first 5 minutes post-exercise.

“Cold-water immersion is an effective cooling method for hot dogs.”

Cool first, transport second

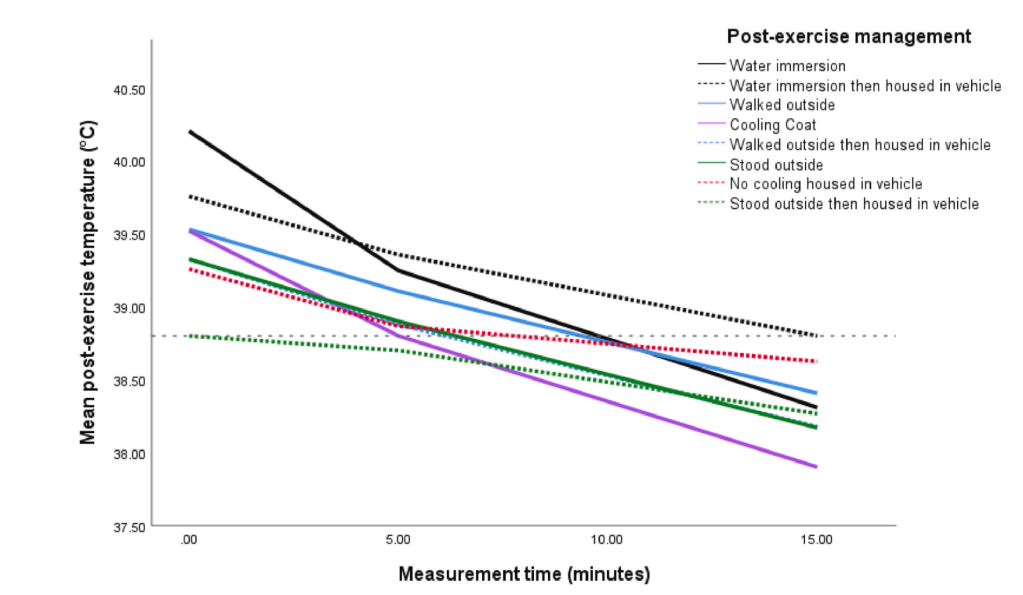

A key finding from our study supports this important message; if your dog overheats for any reason: cool first, transport second. If we review the average (mean) body temperature of all the dogs post-exercise, grouped by their management type (water immersion, walked outside, stood outside, cooling coat, none) and whether or not they were subsequently housed in a vehicle (dotted lines) in the figure below, we can see the hottest dogs were cooled using water immersion. More importantly, we can see no matter the cooling action applied, if the dog was subsequently housed in a vehicle, they cooled less.

The reason dogs cool less once they’re housed in a vehicle is likely due to several factors. The internal car temperature is likely higher than the outside ambient temperature unless the air conditioning is in use, in addition, even with all windows open the dog will experience less air movement inside a vehicle, and air movement is important for evaporative cooling from wet surfaces (after water immersion for example). In our study, by 15-minutes post-exercise, over 80% of the dogs had a normal body temperature, despite many being housed in vehicles. However, consider that all of these canicross events took place in the morning, and mostly during the winter months with cool ambient temperatures. In the summer the internal vehicle temperatures would be hotter, potentially dangerously hot! So if you need to transport a hot dog for any reason we recommend:

- Cool the dog before they enter the vehicle, ideally monitor their body temperature and aim to drop this below 40°C.

- Cool the vehicle interior any way you can, open doors and windows (if safe to do so), or switch on air conditioning.

- Transport the dog in compliance with any legal requirements, but ideally ensure continuous air movement over the dog to facilitate ongoing cooling if they remain overheated.

- In a emergency situation, phone your veterinary practice for advice.

Cool using water – the colder the better

Cooling myths circulate every summer on human, canine and even equine social media sites, but the advice to “only use tepid/lukewarm water” is not supported by evidence. The longer the dog stays hot, the more damage potentially occurring and tissues like the brain and kidney may never recover.

Use whatever water you have available – provided it is cooler than the dog. One study simulating a hot, desert climate demonstrated that dogs can cool even in 30°C water. In our study, 0.1°C water was voluntarily entered by the dogs, resulting in rapid, effective cooling and no adverse effects to the dogs.

Water immersion isn’t without risks. Dogs can drown in water of any temperature! So when it comes to cooling with water there are two options available, but only one is safe for ALL dogs.

Evaporative cooling (application of water – spray, sponge, pour – combined with air movement):

- Appropriate for ALL dogs, regardless of health or consciousness.

- Safe for older dogs, dogs with underlying health concerns, respiratory disease, and even comatose dogs.

Cold-water immersion (or should that be whatever-temperature-water available immersion!):

- Only appropriate for CONSCIOUS dogs, otherwise the risk of drowning is too great.

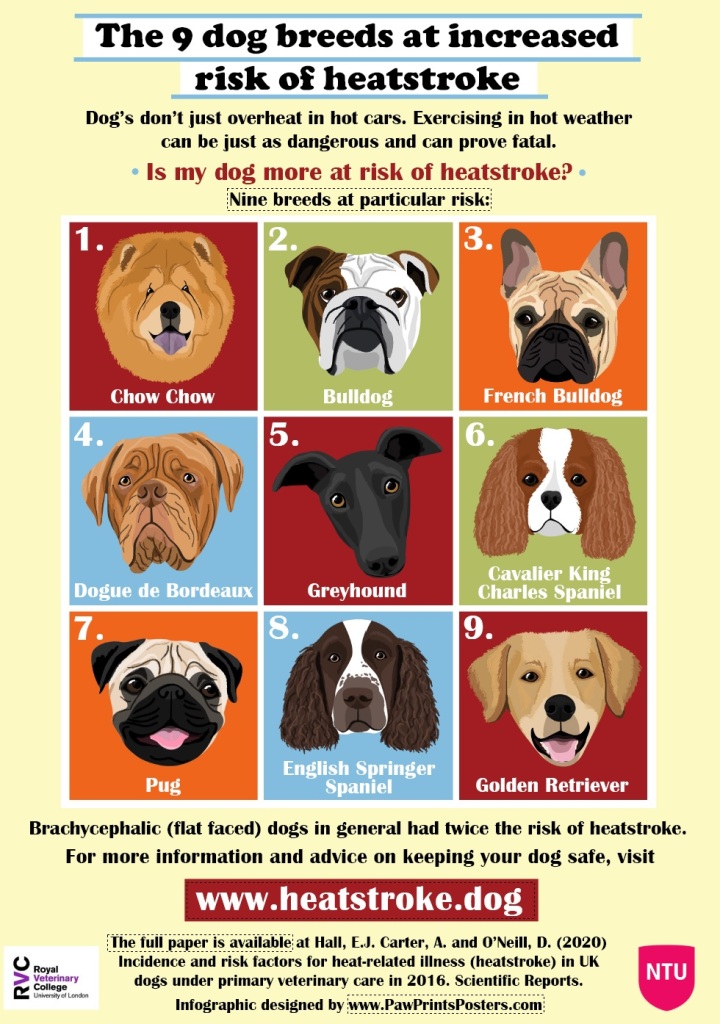

- Most appropriate for healthy dogs, so those younger and fitter, without respiratory disease, brachycephaly (flat faces), or cardiovascular disease.

- If the dog attempts to leave the water, let them.

A final point to finish, if the worst does happen and your dog develops heatstroke (severe heat-related illness) and loses consciousness, they will stop panting. As a result, they will cool more slowly, so you will need to be more aggressive with your cooling measures to bring their body temperature down.

Current advice is to STOP COOLING once the dog’s temperature drops below 40°C (many texts say stop at 39.5°C). This is especially important for older dogs, unwell dogs, and unconscious/comatose dogs as they will struggle to regulate their body temperature.

So as the temperatures in the northern hemisphere start to rise, make sure you have a plan to beat the heat with your dog. If in doubt, don’t go out! But if your dog does overheat, do you have water to cool them?